Why mental health days are vital for RV students

Mental health is of primary concern for students. Here’s why RVRHS should implement mental health days off for students.

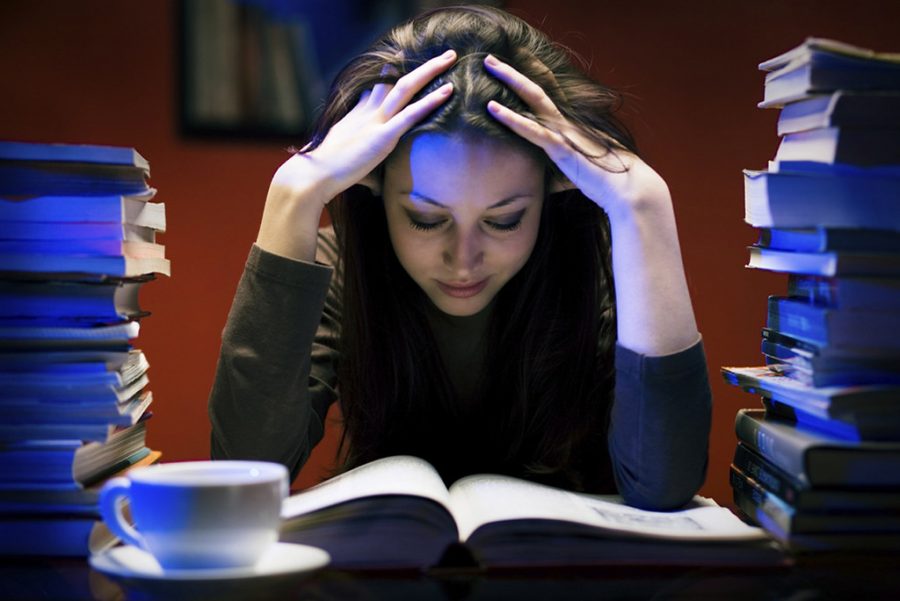

"Student" by UGL_UIUC is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In 2020 students have faced unprecedented challenges.

“I’m so stressed!” This phrase is a perpetual mantra for many high school students. Between financial, social and educational requirements, now in concert with this year’s unique instances such as COVID-19 and the drama of the presidential election, many students are developing anxiety, depression and other mental health issues as a result of too much stress. It is the responsibility of administrators to support their students through these difficult times as much as possible. Therefore, RV must help its students care for their mental health by allowing mental health days off as an acceptable form of excused absence.

“An annual average of about 72,000 adolescents aged 12–17 (10.3% of all adolescents) in 2014–2015 had experienced a major depressive episode in the past year” in New Jersey, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Mental illness is clearly a public health crisis that will affect several RV students and to ignore the mental health of students is negligent. When it is within the school’s realm of power to support its students’ mental health, it is obligated to do so.

The current policy at RV permits students an excused absence for physical or mental illness if a doctor’s note is provided. However, according to a 2018 article for Education Week about school support for student mental health issues, “Just 20 percent of students diagnosed with mental disorders receive mental-health services,’” meaning the other 80% of students cannot take advantage of this policy, as they have no doctor to give them a note. If RV is to implement mental health days off, it must be accessible to all who need them, not just those with access to a doctor who can provide a note.

Additionally, the effectiveness of such legislation is exemplified in Utah and Oregon, where schools have already implemented mental-health days, while several other states are currently attempting to pass similar legislation. States that have passed such laws cite the ending of the stigma surrounding mental health as a major reason for doing so. The current mode of achieving a day off when one’s mental health is suffering entails feigning physical illness in order to avoid an unexcused absence on one’s record. Junior Carter Freudenrich, like many others, has had to pretend to have a more “acceptable” illness to justify their much-needed mental health days off.

“I’ve had to take days where my parents would call the school and be like ‘Oh, they have a headache,’ but I didn’t really have a headache, I just couldn’t go into school that day; I wasn’t able to,” Freudenrich said. Students who resort to such tactics are not compulsive liars or part of a nefarious plot to stay home and slack off, but rather are desperate for relief and will achieve it by working within the broken system.

By addressing mental health, rather than encouraging students to fake an illness to stay out of school, schools can open a conversation with students that can actually improve mental health. Mental health is not a dirty little secret that must be spoken of only in hushed euphemisms and accepted less than phony fevers. As a serious issue affecting RV students, it is an issue that must be pulled into the light and respected.

Freudenrich goes on to enthusiastically support mental health days for students and said, “A lot of people feel guilty that they have to take a mental health day and they feel like they don’t really have a good reason to even though they do.” By legitimizing health days through official approval, the administration can be responsible for helping students who feel like the system does not care for them or accept their illnesses in the same light as physical illnesses. Through acknowledgment of the seriousness of one’s mental health, we can begin to heal that deep-seated embarrassment or feeling of inferiority in students needing support for their mental health stemming from the stigma surrounding mental illness.

“A lot of people feel guilty that they have to take a mental health day, and they feel like they don’t really have a good reason to even though they do,” Freudenrich said.

Contrastingly, opponents of the law erroneously argue that it will give students a false excuse to miss school. However, California State Senator Anthony Portantino, a supporter of mental health days in school, disagrees.

“If you sprain your ankle, we don’t ask how bad it is, or whether it justifies missing work or school,” Portantino said. “We’re not talking about giving students an excuse to stay home – we’re talking about treating this illness as we would any other illness.”

Furthermore, just like sick days for physical illnesses, students would still be required to make up work. This policy would not present a new excuse for lazy kids, but a valid explanation for rest for exhausted or suffering students.

When asked how he would address school officials about mental health, Freudenrich responded, “I’d say it’s very personal, and they should take it seriously… the way teachers and administrators can [help] is by respecting [students] when they need to skip work, or skip that school day, or have an excuse without having to prove that something was going on.”

When school and life seem to demand more of us than we can give, students deserve the ability to care for their well-being. Mental-health days off are crucial in providing students with this much needed opportunity.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Rancocas Valley Regional High School. Your contribution will allow us to enter into regional and national competitions, and will help fund trips to journalism conferences to continue to improve our writing and work!

Alexis Chester is a Managing Editor for The Holly Spirit. She is President of Key Club and Student Council Secretary for the Class of 2022. She is...