The India farmer protests question what is fair in government regulation

Are the new bills helpful in creating new opportunities for farmers, or harmful to a traditional system of agriculture?

March 1, 2021

Since November, tens of thousands of protesting farmers from India’s neighboring states of Punjab and Haryana have demanded the repeal of three-market friendly laws imposed by Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party-led government. The parliament passed the three bills in September, which were then enacted by the president. While Prime Minister Modi termed the reforms a “watershed moment” for Indian agriculture, opposition parties have called them “anti-farmer” and compared them to a “death warrant.”

Anxious farmer groups see the bills as unfair and exploitative, yet pre-reform economists have greatly welcomed the move, saying the new laws will help improve farm incomes, draw investment and technology and increase productivity.

The BBC reports that more than half of Indians work on farms, but farming accounts for barely a sixth of the country’s GDP. Declining productivity and lack of innovation have dwindled progress. Plot sizes are decreasing, as are incomes from farming. The reforms will loosen restrictions around the pricing and storage of farm produce. They also allow private buyers to hoard indispensable commodities for future sales, which only government-authorized agents could do earlier; and they outline laws for contract farming, where farmers adjust their production to suit a specific purchaser’s demand.

One of the most significant changes is that farmers will be allowed to sell their produce at market price directly to agricultural businesses, supermarket chains and online grocers. Most Indian farmers presently sell the majority of their produce at government-controlled wholesale markets, or mandis.

It is unclear how this will play out in reality. For starters, farmers already have the authority to sell to private buyers in many states, but these reforms offer a national framework. Farmers are particularly concerned about the eventual end of wholesale markets and assured prices, leaving them with no back-up option. As long as they are not satisfied with the price offered by the private buyer, they cannot return to mandis or use it as a bargaining chip throughout dealings.

The government claims that the mandi system will stay, and they will not withdraw the Minimum Support Price (MSP) they currently offer. Farmers remain suspicious, and protests have now been the strongest in Punjab and neighboring Haryana state, where the mandi system is strong and the productivity is high, as the government has been able to buy that amount of produce at a set price.

India still has some of the strictest laws around the sale and use of agricultural land, and high subsidies that protect farmers from market forces. The government proposed changes to the bills, and latter offered to suspend them altogether for 18 months even as dealings continued, but the farmers remained firm, stating they will not settle for anything less than a repeal of the reforms.

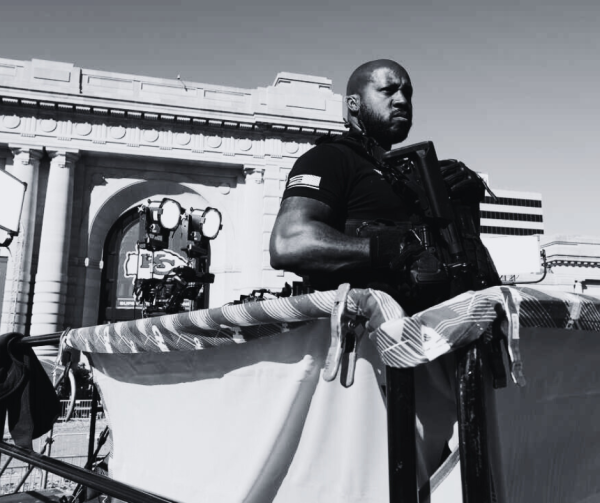

In January, a rally against the laws turned violent, after protesting farmers broke through police barricades to storm Delhi’s historic Red Fort complex. One protestor died and 500 policemen were injured. Farm union leaders defended the violence and blamed the chaos on rogue elements among a peaceful march. Some say that the protestors have lost their legitimacy after the rally, but others say that the farmers should accept the government’s offer to put the laws on hold and return home. Since early February, precautionary measures have been taken to barricade the capital’s border from protestors.

The government’s arrest of 22-year-old climate activist Disha Ravi, accused of helping to create and share an online toolkit that listed peaceful ways the public could support the protests has worsened the situation; mainly because her lawyers claim that she was arrested illegally. Three months in, there is no solution in sight for Indian farmers as their rights are being taken away and their labor is being exploited.

At the time of publication of this piece, the issue continues and has breached American borders. Recently images of Meena Harris, the niece of Vice President Kamala Harris, were burned throughout India, as nationalist protestors warned Indians abroad to “telling her to stay out of their country’s affairs.” The growing sentiments of nativism — and authoritarianism under Modi’s rule — continue to create a hotbed of conflict in the already volatile region.

Glynnis Bastas • Mar 1, 2021 at 4:11 pm

Awesome job Janjiiii!!!!!!!!!